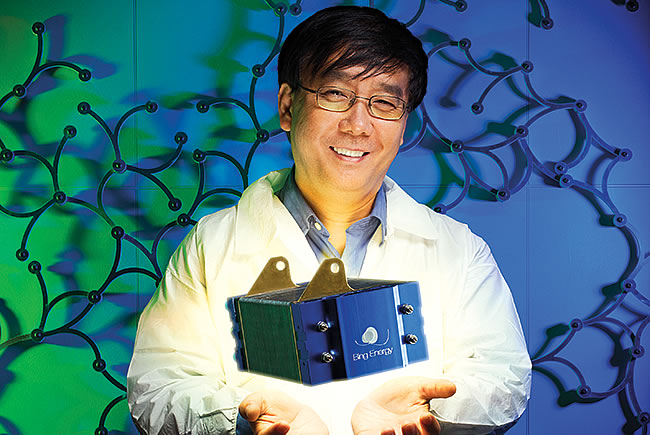

Bing Energy — founded on the work of FSU researchers — offers a tantalizing glimpse into a hydrogen-powered future.

Lilly Rockwell | 5/27/2014

In 2004, Florida took a stab at establishing itself as a leader in hydrogen-fuel research. The state created a public-private partnership that trotted out a package of demonstration projects and tax incentives meant to provide a road map for hydrogen-fuel business development in Florida. The Florida Hydrogen Business Partnership’s efforts didn’t generate much momentum, however, and two showpiece hydrogen fueling stations the group helped set up in Florida have since shut down. (Today, there are only 10 hydrogen fuel stations in the U.S., according to federal data.)

A blip of hope for hydrogen in Florida began to take shape two years later, however, during a lunch at a Tallahassee Subway restaurant between two colleagues — both Chinese expatriates — at Florida State University.

Ben Wang was a founding director of FSU’s High Performance Materials Institute, where he had conducted pioneering research into uses for Buckypaper, a material made of microscopic carbon tubes 1/50,000th the diameter of a human hair. Sheets of Buckypaper are 250 times stronger than steel but 10 times lighter. The material, which conducts electricity about as well as silicon, holds big promise for a host of engineering applications in aircraft, prosthetics, building construction, ships, body armor and cars.

Jim Zheng, meanwhile, was a professor in FSU’s department of electrical engineering. He was focused on studying alternative energy sources, including fuel cells that combine hydrogen and oxygen to create a chemical reaction that generates electric current [“Fuel Cell Science”].

At the 2006 Subway lunch, the two discussed various applications for Buckypaper before figuring out that “this could be a pretty good way to develop a fuel cell,” Zheng says. “That was my idea.”

Using Buckypaper in fuel cells appeared to have two big advantages: One, it could make the cells lighter. More important, they thought, the properties of Buckypaper could reduce the amount of expensive platinum the cells needed to produce the chemical reaction.

Using Buckypaper in fuel cells appeared to have two big advantages: One, it could make the cells lighter. More important, they thought, the properties of Buckypaper could reduce the amount of expensive platinum the cells needed to produce the chemical reaction.

Over three years of research, Zheng and Wang, with the help of post-doctorate student Wei Zhu (now Bing’s R&D director), developed a cell that met a technical goal set out by the U.S. Department of Energy: It could sustain a vehicle for 5,000 hours of running time — the equivalent of 100,000 miles. Zheng says the Buckypaper cell also appeared to be more stable than existing cells, with a longer lifespan.

By late 2009, Zheng started to think his invention should be in the hands of people who knew how to run a business. He called up an old college friend — Harry Chen — and that led to the formation of Bing Energy. (Wang, now an engineering professor at Georgia Tech, was not among Bing’s founders and has no role in the company.)

Today, the company’s fuel cells use less than half the platinum of traditional fuel cells. While it costs about 30 cents per square centimeter to build a Bing cell, about the same as a traditional cell, Bing CFO Dean Minardi says “our durability is more than two times as much,” cutting the life-cycle cost of the Bing cell in half.

Headquartered in a technology park in Tallahassee, Bing’s 10 employees include the executive team and other high-level workers with Ph.D.s who continue to do research and engineering work.

Some at Bing foresee a day when electric cars will be powered not by electricity stored in batteries, but entirely by power generated by hydrogen fuel cells.

All acknowledge that that day is still a long way off, however. And for the forseeable future, Bing’s transportation-related efforts in the U.S. will focus on producing fuel cells that don’t provide a primary power source for vehicles. Instead, the Bing cells will help extend an electric vehicle’s range by partially recharging its batteries as the car operates.

In mid-April, Bing Energy purchased the assets of a company in West Palm Beach called EnerFuel — giving Bing access to the company’s 40 patents and prototypes of vehicles with hydrogen fuel cells used as range extenders.

In the rear parking lot of Bing’s headquarters, Minardi shows visitors a green EnerFuel-labeled car that gets its primary power from batteries but is equipped with a Bing fuel cell range extender that can extend an electric vehicle’s range from 30 miles to 150 miles.

Minardi says the company plans to keep the EnerFuel brand and target fleet operations involving buses and package delivery companies — vehicles that can be recharged and refilled every night.

In time, use of hydrogen will grow, Minardi says. Natural gas filling stations, which are popping up as vast reservoirs of natural gas are unlocked in the United States, can easily be retrofitted to add a hydrogen fuel pump.

Meanwhile, Bing plans to earn revenue by selling its Buckypaper fuel cells — known as “membrane electrode assemblies” — to telecommunications companies in China for use as backup power generators for cell phone towers. Most of the current towers — “there are 1.3 million cell towers in China,” Minardi says — rely on inefficient, polluting backup generators that use diesel or lead acid batteries. Bing’s fuel cells are lighter and more compact than the batteries, which have to be replaced at least once every five years, or the diesel generators, which have to be run once a week for an hour and drained every six months.

“A 500-pound fuel cell makes no vibrations, no noise, and you have to turn it on and off maybe once or twice a month,” Minardi says. Bing’s fuel cells cost around $10,000, which Minardi says makes them competitive with the existing backup systems.

Most of Bing’s manufacturing activity is in China, which gave the company a major incentive deal to locate a manufacturing plant in Rugao, a city of 1.4 million people 125 miles northwest of Shanghai. In exchange for a 40% stake in Bing’s Chinese subsidiary, the Chinese government gave Bing a 110,000-sq.-ft. three-story manufacturing facility, a 30,000-sq.-ft. dorm for employees and an investment of $7.5 million over five years. The money was earmarked to pay for equipment and other capital investments.

In Florida, Bing produces the “core intellectual property,” including the Buckypaper and then ships incomplete fuel cells to China to be assembled. The completed fuel cell, or membrane electrode assembly, is then sold to end-users.

Minardi says a big telecommunications company in the U.S. is testing Bing Energy’s fuel cells as backup power generators, but the Chinese market remains more promising than the American market for the moment. “China is growing fast,” he says. “They need cell phones. They need power, but they can’t run diesel generators. They need cleaner power. In the U.S., it’s less mission-critical because we have a very stablepower grid, and we don’t have the pollution.”

Navigant Research predicts the stationary fuel cell market will grow from $1.7 billion in 2013 to $9 billion by 2022, and Minardi says Bing intends to compete in the U.S. as well — and manufacture fuel cells domestically. “The way we are set up is as the market in the U.S. starts to get going, we will build it right here in Tallahassee,” Minardi says.

By the end of 2015 he predicts Bing will be “cash flow and profit positive.”

Meanwhile, Minardi says he’s optimistic that the most profitable way for Bing to tap into the automotive industry is by focusing on fuel cells as range extenders. Toyota is looking at incorporating fuel cells into its electric cars to create a new kind of hybrid, Minardi says. “We’re working on an order for range extenders right now,” Minardi says.

Ultimately, he says, the fuel cells’ promise for widespread automotive use endures: The only pollution they generate “is warm water.”